A human's moral worth is, like, less than a shrimp

A ChatGPT-assisted back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Spicy take, huh?

Turns out that, according to a relatively quick calculation, an average human is worth much less than we initially thought, and a shrimp is worth much more than we typically think. Humans are terribly bad in terms of producing harm towards other beings. Their moral worth seems, uh… *checks math* negative.

My motivation.

Roughly 440 billion shrimp are being killed each year for food, making them one of the biggest victims of our food production system.

Yet shrimp welfare is one of the memes about animal welfare on the internet, even within the Effective Altruism community. We have an organization, the Shrimp Welfare Project, that cares about making conditions for shrimp better. Particularly, they make the painless death of shrimp extremely affordable. Yet, it has become such a meme because only a very narrow proportion of the human population actually cares about shrimp, so the idea that we should morally care about shrimp is mocked quite often.

Yet, as often with issues having to do with the moral vanguard, which in the past included all of animal rights, we typically start with mockery, but over time, the majority of people are simply shown to be wrong. They based their judgements in prejudice, the status quo, and an unwillingness to engage with argument, rather than daring to question the received wisdom of their narrow moral circle.

Of course, I won’t convince you of the case for shrimp welfare if you’re not up to speed on the more mainstream case for animal rights or welfare. It’s simply too far outside of your Overton Window of things you’re willing engage with or take seriously. It is likely to sound ludicrous to you. For those who aren’t acquainted with the discussion, you might want to get started with people like Peter Singer, Michael Huemer, Melanie Joy, or perhaps simply check some videos on the conditions of factory-farmed animals to get you to care about more mainstream animals such as cows, pigs, and chickens. Go out there exploring, take it at your own pace, and come back here once you’re willing to take more “out there” animal welfare concerns seriously. I used to meme about shrimp welfare too, it took me years to shift my moral concern from chickens to shrimp! So I wouldn’t judge you negatively for it, if you approach these questions without mockery and with an open mind.

Lately, a growing contingent of us researchers in moral philosophy has argued in favor of caring about the welfare of invertebrates, including shrimp welfare. These people include some bloggers like Brian Tomasik, Bentham’s Bulldog, and myself. Also, people like Jonathan Birch and Jeff Sebo have developed precautionary principles for why we might aim to reduce invertebrate suffering, even if we are not completely convinced about whether they can suffer (given their relatively low neuron count, and empirical uncertainty in the science) or whether suffering is the central pillar of ethics (given moral uncertainty).

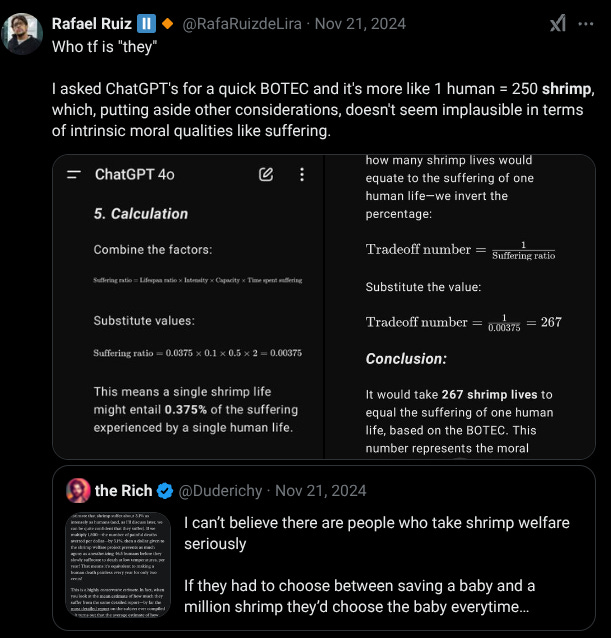

Anyway, this post is an extension of this tweet I made some months ago, replying to a skeptic about animal welfare:

In response, I went and asked ChatGPT and did back-of-the-envelope calculation (BOTEC). The results surprised me, and I ended up chatting back and forth with a lot of people who believed I was going too far. It was an interesting thread!

So I recently went back to it, and expanded upon my ChatGPT-assisted BOTEC. Turns out, if we incorporate some other factors, the stuff looks even worse for humans than I anticipated. This was my conversation with ChatGPT, lightly edited for brevity.

Keep in mind that this is casual and done in a couple of hours of my time, so don’t take it deadly seriously. I’d love to hear if you think I went wrong somewhere, and if so, where and why.

But, overall, I’d like for people to take it more seriously than I expect they will. I hope it’s (vegan) food for thought.

Initial BOTEC.

Me: “What percentage of human suffering might a shrimp life undertake? Give me a BOTEC.”

ChatGPT: This requires speculative reasoning about comparative suffering. To make a rough guess, one could consider the following aspects:

Nervous System Complexity: Shrimp have simpler nervous systems than humans, with fewer neurons and less capacity for complex pain or emotional experiences. While they can likely experience nociception (basic pain response), they are unlikely to experience suffering as richly or deeply as humans. Shrimp may experience environmental stress, predation, or discomfort, but they do not experience psychological suffering in the way humans do (e.g., anxiety, existential dread, or chronic emotional pain).

Humans experience physical and psychological suffering, whereas shrimp are assumed to experience only physical suffering.

Assign 50% of the weight to physical suffering for humans and 100% to shrimp, given that they lack emotional complexity.

Thus, a shrimp’s suffering capacity might be 50% relative to human suffering.

Lifespan: A shrimp's life is much shorter, typically 1 to 6 years, depending on the species. The duration of any suffering is, therefore, inherently limited.

Average human lifespan: 80 years.

Average shrimp lifespan: 3 years (weighted average across species).

Ratio: A shrimp lifespan is 3.75% of a human's.

Time Spent in Suffering:

Assume an average human spends 10% of their life actively suffering (e.g., in pain, distress, or significant hardship).

Shrimp raised in aquaculture or caught in the wild might spend 20% of their life in stressful or painful conditions, due to poor farming conditions, predation risk, and handling at death.

Ratio: Shrimp experience suffering 2x as frequently as humans during their shorter lives.

Intensity of Suffering: The intensity of pain perception in shrimp is likely much lower than in humans, given their evolutionary differences.

Shrimp lack complex brains and emotions, so we assume their maximum pain intensity is 10% of a human's (a conservative upper bound).

This assumption is based on nervous system complexity, which is orders of magnitude lower than a human’s (~100,000 neurons for a shrimp vs. ~86 billion for humans).

Initial Calculation.

Combine the factors:

Suffering ratio = Lifespan ratio * Intensity * Capacity * Time spent suffering

Substitute the values:

Suffering ratio = 0.0375 * 0.1 * 0.5 * 2 = 0.00375

This means a single shrimp's life might entail 0.375% of the suffering experienced by a single human life.

Me: “So if it's 0.375% like you said, what's the tradeoff number between humans and shrimp?”

ChatGPT: To calculate the tradeoff number—how many shrimp lives would equate to the suffering of one human life—we invert the percentage:

Tradeoff number = 1 / Suffering Ratio

Substitute the value:

Tradeoff number = 1 / 000.375 = 267

It would take 267 shrimp lives to equal the suffering of one human life, based on the BOTEC. This number represents the moral tradeoff, assuming the 0.375% estimate holds. If applied to ethical decision-making, this figure can guide evaluations of interventions (e.g., reducing shrimp farming) relative to efforts focused on alleviating human suffering.

Adjusting for Uncertainty.

Me: “Let's say I'm 30% confident that shrimp are conscious and believe there's 40% that consequentialism is true, how do the numbers look like now?”

ChatGPT:

Adjust for Empirical Uncertainty (30%).

The BOTEC estimate suggested 267 shrimp = 1 human, based on a 0.375% suffering equivalence. If you are only 30% confident that shrimp are conscious, the suffering equivalence estimate should be discounted by this probability.

Adjusted suffering ratio = 0.00375 * 0.3 = 0.001125

This means 1125 shrimp lives would now be equivalent to one human life, assuming full confidence in consequentialism.

Adjust for Consequentialism Confidence (40%).

Since you're 40% confident that consequentialism is the correct moral framework, the suffering equivalence should be discounted further by this probability:

Adjusted suffering ratio = 0.001125 * 0.4 = 0.00045

New Tradeoff.

This means the new tradeoff number is:

Tradeoff number = 1 / 000.45 = 2222 shrimp per human.

Given your confidence levels, the suffering of 2222 shrimp lives would equate to the suffering of 1 human life. This adjusted number reflects:

Epistemic humility about shrimp consciousness.

Normative uncertainty about consequentialism as the correct moral framework.

A significantly higher threshold for justifying tradeoffs compared to the initial BOTEC.

Accounting for Other Factors.

Me: “What other moral or practical considerations might I be missing?”

ChatGPT:

The Tractability of Reducing Suffering.

Reducing human suffering is often harder than reducing shrimp suffering because:

Humans have complex needs (e.g., political rights, healthcare, education).

Shrimp welfare interventions (e.g., stunning before slaughter, better farming conditions) might be low-cost and high-impact.

Adjustment: If you prioritize cost-effective suffering reduction, you might prioritize shrimp interventions even if their suffering is discounted per individual.

Flow-Through Effects.

Human lives have broader moral impact: Humans can shape policies, influence ethics, and improve welfare for all sentient beings, including shrimp. If saving a human life leads to policies that improve factory farming conditions, it might outweigh the suffering of many shrimp.

Adjustment: If human survival has high flow-through benefits, this might lower the moral importance of shrimp suffering in comparison.

Psychological and Social Factors.

Public Perception Matters: Many people dismiss concerns about shrimp welfare. If advocating for shrimp dilutes focus on more winnable animal welfare causes (e.g., chickens, pigs), it might be strategically suboptimal.

Neglectedness Consideration: Shrimp welfare is still a relatively neglected cause in animal advocacy, making it more cost-effective per unit of suffering reduced.

Adjustment: If you prioritize neglected and tractable causes, shrimp might be more important than their suffering ratio suggests.

The Meat Eater Problem, or, where things get dark.

Me: “So let’s talk about those flow-through effects. People can have negative externalities too. What about the “meat eater problem”, the rise of consumption of animal products if we focus on people? What would you say is a reasonable BOTEC tradeoff factor, trying to account for a variety of extrinsic factors (like people eating meat, but also like protecting other sentient beings)?”

ChatGPT: You're absolutely right that humans have negative externalities, particularly in how they impact other sentient beings. The “meat-eater problem” (the argument that saving human lives increases animal suffering by increasing meat consumption) and other flow-through effects (like policy change, innovation, or institutional reform) need to be factored into our BOTEC.

Adjusting for Negative Externalities (the Meat-Eater Problem).

One major issue with focusing on human welfare is that humans cause suffering indirectly:

The average global meat consumption is ~43 kg per year (~100 lbs).

The average lifetime meat consumption for a human (assuming 80 years) is ~3,440 kg (~7,500 lbs).

This corresponds to killing 30 cows, 900 chickens, 40 pigs, and tens of thousands of shrimp/fish.

So, saving a human life (with no dietary change) may create a massive net negative in terms of animal suffering.

BOTEC for Meat-Eater Effect on Shrimp.

About half of all seafood consumption comes from shrimp.

If we assume a lifetime meat consumption of ~1,000 kg of seafood per human, and shrimp are 20% of that, a single human life might cause the death of thousands of shrimp (since they are very small).

Conservative estimate: If one human’s seafood consumption means 5,000 shrimp deaths, then saving a human life means adding at least 5,000 shrimp deaths.

If we stick with the original suffering equivalence (2,222 shrimp = 1 human), then each human saved now causes more harm than their suffering offsets.

So, we now subtract 5,000 shrimp from the original tradeoff to account for the additional suffering caused by their consumption:

Corrected Tradeoff = 2,222 - 5,000 = -2,778

Since the number is negative, this means that saving a human is actually a net harm in terms of shrimp suffering! (Yes, that’s negative moral worth. Humans are net-negative, because their consumption causes more shrimp suffering than their own suffering is worth.)

What This Means.

Humans are now morally net-negative because they cause more shrimp suffering than they offset.

Instead of it taking 2,222 shrimp to equal one human, we now see that each human is worth “minus” 2,778 shrimp in moral terms.

This means that from a shrimp-focused suffering perspective, it would actually be better (in shrimp terms) to not save a human life.

Humans are net-negative due to their shrimp consumption unless they contribute significantly to reducing animal suffering.

What about Positive Shrimpact?

Me: “Let’s now adjust for those positive externalities.”

ChatGPT: On the flip side, humans can contribute to moral progress:

Some humans reduce animal suffering through activism, policy work, or research.

If one saved human promotes veganism or animal welfare, they could offset their own meat consumption and influence others.

Many consequentialists argue that human progress (e.g., lab-grown meat, AI alignment for moral concern, animal welfare policies) could vastly reduce suffering long-term.

Estimating Positive Externalities.

Let’s assume 1 in 1,000 humans saved has an impact equivalent to preventing millions of shrimp deaths via systemic change.

However, 99.9% of saved humans do not make any meaningful contribution to reducing animal suffering.

What fraction of saved humans actually become effective advocates?

If 1 in 1,000 people becomes a serious animal welfare advocate (not just vegetarian, but actively reducing suffering), that’s 0.1%.

If 1 in 10,000 people has an industry-level impact, that’s 0.01%.

Case 1: The Dedicated Vegan. A dedicated vegan advocate might influence dozens to hundreds of people to reduce or eliminate seafood from their diet over a lifetime.

Let’s assume a strong advocate convinces 100 people to stop eating shrimp.

If each of those people would have eaten 5,000 shrimp in their lifetime, that’s: 100 * 5,000 = 500,000 shrimp deaths prevented

Case 2: The Industrial Campaigner. Groups like The Humane League, CIWF, and Rethink Priorities work on shrimp welfare improvements.

Corporate reform campaigns (e.g., stunning before slaughter) affect millions or billions of shrimp.

A single advocate could contribute to policy changes that reduce suffering for millions of shrimp.

Let’s conservatively estimate that a policy-focused advocate prevents suffering for 1,000,000 shrimp over their career.

Case 3: The Future Food Advocate. Someone working on alt-seafood, cultured shrimp, or welfare policy might shift entire industries.

Let’s assume they contribute to large-scale reduction efforts impacting tens or hundreds of millions of shrimp.

Even if their individual contribution is only 0.1% of a major industry shift, that could still prevent 1,000,000 shrimp deaths.

Based on these real-world mechanisms, a highly effective shrimp advocate plausibly prevents between 500,000 and 1,000,000 shrimp deaths in their lifetime.

If 1 in 1,000 saved humans prevents 500,000 to 1,000,000 shrimp deaths, the expected value per saved human is 500 to 1,000 deaths prevented per saved human. Let’s take 750 as the average.

Final BOTEC.

Each saved human causes 5,000 shrimp deaths via seafood consumption.

Each saved human prevents only 500 to 1,000 shrimp deaths through the expected advocacy of one in one-thousand vegan, industry, or future food advocates. Let’s take 750 as the average.

If so, on average, each human causes 5,000 shrimp deaths but prevents 750.

Final Result, Net Impact per Human: -5,000 + 750 = -4,250

Each saved human causes 5,000 shrimp deaths but prevents 750. Humans, on average, have negative moral worth in shrimp terms.

Even after accounting for positive externalities, saving a human still increases net shrimp suffering.

Since the meat-eater effect is so strong, this suggests that only highly altruistic humans are net-positive in shrimp terms.

Thus, for the average human, the tradeoff is still negative, but for one who engages in significant activism, the tradeoff could return to the 5,000–10,000 shrimp per human range.

Me: “What about other animals?”

ChatGPT: The problem extends beyond shrimp. Humans drive massive suffering for:

Chickens (~70 billion killed annually, often in horrific conditions).

Fish (~1-2 trillion caught and farmed per year, usually without welfare considerations).

Insects (trillions killed in agriculture, with little attention given to their suffering).

Based on the BOTEC calculations, the approximate suffering tradeoffs are:

1 human life ≈ 50,000 chickens in suffering terms.

1 human life ≈ 889 fish in suffering terms.

1 human life ≈ 444,444 insects in suffering terms.

Given the sheer scale, the argument generalizes: humanity has been, on balance, an engine of suffering for nonhuman animals.

Practical Takeaways.

So that’s what ChatGPT has to say. Here are my takeaways from that conversation:

Humans are plainly evil. Humanity hasn’t been worth it, so far. Consuming animals causes more moral harm than you, as a human, are worth in moral terms.

Most humans contribute more to suffering than they alleviate. This doesn’t mean individual humans can’t be good, but as a species, we have a lot of work to do.

You should be vegan and support any practices to reduce animal suffering that you can.

But we can, hopefully, turn things around. All meat-tasting products should be replaced with alternatives (lab-grown meat, plant-based, etc.).

Help the shrimp. Shrimp suffer in massive numbers and are extremely neglected in animal welfare efforts. Some of the most cost-effective shrimp welfare interventions focus on:

Stunning before slaughter (prevents inhumane slaughter suffering).

Improving water quality in shrimp farming (reduces chronic suffering).

Reducing stocking densities (shrimp have more space and less stress).

These interventions are incredibly cheap: $0.001 - $0.10 per shrimp life improved. With $5,000 (same as saving a human life through global health interventions), you could improve conditions for 50,000 - 5,000,000 shrimp (depending on the intervention). This reduces suffering far more than saving a human would.

So consider donating to the Shrimp Welfare Project. Even donating a small amount will offset all the harms you’ve done to shrimp in your entire life!

You should care about bugs, too. I think bugs are important and neglected too. You can read more about it here.

Protect the long-term future. If we care about reducing suffering at scale, we should ensure that the long-term future goes well. Humanity can’t go on like this.

Turns out that conversations about ethics with ChatGPT are much more civilized than conversations with people on the same topic. Which is a bit of a shame.

UPDATE.

The Messy Math of Wild Animal Suffering.

Out of a discussion of 20 long comments, the one that changed my mind the most was the shortest one, the one by Bentham’s Bulldog saying that, actually, humans are morally good, because wild animal welfare is net negative, and humans are destroying the environment, so less animals suffering in the wild exist.

It is hard to me to compute exactly how much benefit versus harm that is, so the net calculation is extremely messy.

But it seems that *IF* animal lives in the wild are net negative, and *IF* we could change environments so that they don't exist anymore, it would be a morally good thing to support their non-existence, rather than existence into a life of mostly suffering. Following this logic, the ultimate utilitarian position might indeed be that *neither* factory-farmed animals nor wild animals should exist, at least under the present conditions of widespread suffering. I find that conclusion troubling, though philosophically correct.

Forced Sterilization of People is *NOT* a conclusion I’d advocate.

Some other people have said that the ultimate conclusion of my post is forced sterilization of people or something like that. That doesn’t seem right.

As Ozy Brennan has replied about these kinds of comments: “We are apparently postulating a world where animal advocates have the power to forcibly sterilize large numbers of human beings, but can’t force them to eat tofu.” We defenders of animal rights aren't even able to enforce practices such as *veganism*, so much less anything such as the *forced sterilization of people* (which would be unnecessary with veganism). And veganism would be much easier. So the practical considerations don't even follow.

Ultimately, I do believe that we can turn things around (with the popularization of artificial meat, and in the long term, enforcing veganism through democratic means, etc.). Humans' capacities for technologies and for changing the environment are quite powerful.

But it isn't our intrinsic moral worth that turns things around, but the morally extrinsic, cognitive abilities of making new technologies and changing our environment.

Recommended Readings.

Bentham’s Bulldog (2024). - The Best Charity Isn’t What You Think.

Bentham’s Bulldog (2024). - Rebutting Every Objection To Giving To The Shrimp Welfare Project.

Bentham’s Bulldog (2024). - Betting On Ubiquitous Pain.

Bentham’s Bulldog (2022). - May The Factory Farms Burn: Factory farming is the worst crime in history.

Anthis, J. (2022). The Future Might Not Be So Great.

Sebo, J. (2023). The Rebugnant Conclusion: Utilitarianism, Insects, Microbes, and AI Systems. Ethics, Policy and Environment 26 (2):249-264.

Sebo, J. (2025). The Moral Circle. (book)

Sebo, J. (forthcoming). Moral Circle Explosion in The Oxford Handbook of Normative Ethics.

Fischer, B., Sebo, J. (2024). Intersubstrate Welfare Comparisons: Important, Difficult, and Potentially Tractable. Utilitas 36 (1):50-63.

Fischer, B. (ed.) (2024). Weighing Animal Welfare: Comparing Well-Being Across Species. (book, free to download)

Birch, J. (2024). - The Edge of Sentience: Risk and Precaution in Humans, Other Animals, and AI. (book, free to download)

Tomasik, B. (2009). Do Bugs Feel Pain?.

Plant, M. (2022). The Meat Eater Problem. The Journal of Controversial Ideas, 2(2).

Huemer, M. (2018). Dialogues on Ethical Vegetarianism. (book, free to download)

Shouse, T. (2025) Shrimp Have Moral Value.

Wollen, A. (2025) The Hinge of Insect History.

Wollen, A. (2025) Lyman Stone's intellectually molested critique of shrimp welfare.

Ruiz, R. (2024). Impartialist Sentientism and Existential Anxiety about Moral Circle Explosion.

a few miscellaneous & kinda hapazardly formed thoughts:

i think a few liberal assumptions were made which can swing things the other way—namely the confidence that shrimp are sentient, or just how much they feel.

in any case, humans seem to have a net positive benefit if you account for other factors. for instance, insects suffer immensely painful lives (if we have some confidence in their sentience). humans kill a lot of insects prematurely before they live the rest of their painful lives through climate change and stuff. this could mean humans have a net positive moral impact if you account for insect pain.

finally, I have a strong inclination that you're underselling the positive externalities per human. i.e., the existence of human society entails the unprecedented possibility that life might eventually become net positive in utility—that is to say, eventually, human society might progress to the point where humans increase utility. so accounting for long-termism, improving human society may have a much higher positive externality for shrimp than you're considering.

Because insects live mostly bad lives and humans reduce insect populations so much, I suspect the average person has a positive impact on welfare.