I coexist between three different online spheres. One is the online leftist space, the second is Effective Altruism and online rationalism, and the third is analytic moral and political philosophy. Anyways, if the previous post leftistly praised the virtues of "woke" made the Effective Altruists and moral philosophers upset, this one might make some of the leftists upset, and the Effective Altruists, online rationalists, and moral philosophers happy.

This post is actually a fairly typical Effective Altruist and online rationalist idea, but I think it's worth reiterating: analogies, metaphors, fiction, and slogans are often overrated, misleading or dangerous tools for argumentation. While they can be useful for conceptual exploration or sparking new ideas, they often become a problematic crutch when most people rely on them to justify positions without understanding whether the mapping between the analogy and reality actually holds up.

Metaphors and Analogies.

Let’s start with metaphors and analogies, which is when you say that X is like Y. They usually highlight one similarity between two things in order to make a point, but almost always ignore their many differences. In very casual conversation or when trying to think through an issue, this use is mostly fine, since it's how we make sense and grasp unfamiliar ideas for the first time. But in moral and political arguments, analogies can be more misleading than illuminating. Potentially, they are actually harmful when they are used to rationalize our biases. Many analogies hinge on pure vibes rather than rigorous similarity, creating the illusion of argument rather than providing actual justification.

For example, I've heard metaphors like: “Coming to my country is like coming to my house” to justify restricting immigration. And, I'm sorry to be the pedantic philosopher, but what does that actually mean? Sure, in both cases there’s an idea of "someone else entering a space." But a country might not be a house in the relevant sense, because its functions, obligations, and moral stakes are very different! The analogy hinges on the intuitive sense of "private space" but I think doesn’t actually stand up to scrutiny.

Some others:

“Managing the economy is like managing a household budget.”

Why it feels compelling: because it feels “common sense”, once again, it analogizes the house and the state.

The problem: I’m no economist, but a state that issues its own currency doesn’t face the same temporal, liquidity, or risk constraints as a family. The analogy hides how monetary policy and an international economy works.

“Taxation is theft.”

Why it feels compelling: Invokes common sense intuitions about non-consensual taking of your possessions (if you read some libertarians, they use or build an entire political system on these kinds of intuitions, if you read Robert Nozick, he mostly presupposes them)

The problem: I think this collapses or skips ideas about legitimate authority, consent, and public-goods provision into a narrow frame of property rights that I think is probably mistaken. In the case of Nozick, it seems like it pre-judges the moral boundaries of the individual rather than arguing for them.

Using the trolley problem as guidance for many real-world problems.

Why it feels compelling: In the philosophy classroom, we often want to isolate sharp and crisp moral intuitions, rather than bringing in the mess and uncertainties of policies in the real world. Students learn the style without being explained the methodology behind it.

The problem: In complex systems like the real world, there are empirical uncertainties to policy (e.g. whether allowing or banning abortion or prostitution will lead to higher welfare), and option sets are usually much broader than trolley-like stylized choices.

“Anything short of systemic change is futile” / “Helping developing countries without abolishing capitalism is like putting a band aid on a wound”, as a critique of suggestions such as cash-transfers, carbon pricing, etc.

Why it feels compelling: Partly because it redirects the problem and lets people go on with their lives without changing their lives a single iota, allowing them to go on vacation or buy the newest phone without guilt.

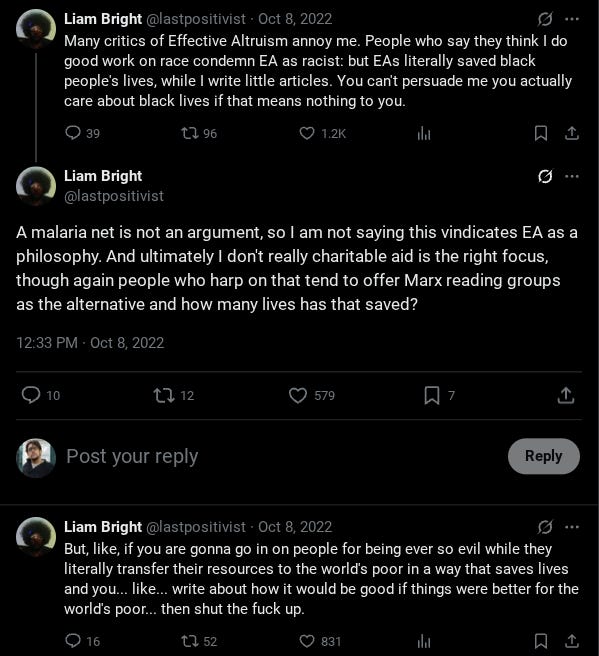

The problem: Defenders of cash transfers or carbon pricing usually don’t sell their idea as the sole panacea, yet these methods do more to help the poor than most leftist reading groups on Marx. The comparison group should probably be the status quo of private individuals not doing anything about it, not a far-off socialist utopia that is extremely unlikely to come. It also breeds all-or-nothing attitudes that lead to political polarization of looking for extreme solutions, rather than actually caring about the economic growth over the long-run of several decades that many countries have experienced, and that has lifted billions out of extreme poverty.

The problem is that many people stop at the vibe of “the first analogy that comes to my mind feels right” and don’t move on to the important step of justifying why the analogy is relevant, close enough, or the best analogy to use to the real-world case to be the most illuminating analogy that could be used there. It's precisely that next step, the mapping out the similarities and differences, that most analogical arguments skip, yet it might be the most important!

To be clear, again, I'm not against using analogies or metaphors altogether. They're great for simplifying a topic to a broad audience (although with some caveats, there are perhaps too many people that think that they understand quantum mechanics in terms of simplified pop-science metaphors), and useful for teaching, triggering creative insights, or sketching out early drafts of new ideas. But if you want to argue that “X is like Y”, you need to do the work, by specifying the dimensions of similarity, acknowledging where the analogy breaks down, and showing why the similarities are the ones that matter here. Otherwise, the analogy is just misleading rhetoric, not reason.

Fiction.

You can use fiction to “justify” anything. You can write a fiction book showing how wonderful communism is, or write a different book showing how it is a hellscape. The same with capitalism, libertarianism, egalitarianism, or with basically any idea. The fact that a fiction book exists on a topic doesn’t refute any similar-seeming ideas if applied in the real world. Yet people use fiction as if it refutes any political view.

Some key examples:

1984 for arguing against any form of surveillance policy or government intervention.

Why it feels appealing: portrayals of dystopia easily cause fear, and fear is one of the strongest emotions.

The problem: People think that all forms of surveillance or state intervention in our lives will inevitably lead to totalitarianism, which completely short-circuits their capabilities for doing accurate cost–benefit analysis of policies regarding these topics. Any modest new policy or regulation is “literally 1984”.

Frankenstein or Brave New World for framing technology as dystopian.

Why it feels appealing: the idea of “Playing God” as this religious hubris narrative has been reinforced throughout the generations. Emotions of disgust towards the weirdness of technology drive moral aversion.

The problem: Simply put, lots of technologies have been amazing. Most people used to live in extreme poverty, lack access to basic healthcare, heating, plumbing, electricity, etc. Half the children simply died before becoming adults. Many (most?) technologies feel a bit alien and icky in the beginning, but we can get used to them pretty fast, and they won’t even seem so weird to future generations that grow up with them. This gut feeling has been very costly in the history of humanity.

Slogans.

Many moral and political debates are derailed by thought-stopping slogans. Take, for example, typical appeals to the “sanctity of life.” While this phrase can be emotionally powerful, it tends to shut down rather than invite to further careful analysis, such as bioethicists saying that we should invest the same amount of resources in saving a 90-year-old as a five-year-old. The slogan is used to imply that there is some inherent, inalienable, non-negotiable value to life that resists qualification, balancing, or tradeoffs, regardless of context or consequences. But rarely is this position argued for in a rigorous sense. It’s simply presented as a self-evident truth, and it worsens the quality of the moral discussion.

The problem is that moral questions are often complex and involve trade-offs. Even if we grant that life has significant moral worth, it doesn’t follow that all lives are of equal worth in all circumstances or that no other values ever override life’s sanctity. Our wider views on contexts such as self-defense, war, or triage in medical emergencies show that we do, in practice, weigh lives against other values or other lives. If we take the “sanctity of life” slogan at face value, it forbids engaging with these real-world situations, leading to inaction since all situations would require a rights violation in some circumstances.

Moreover, these thought-stopping slogans can obscure the underlying disagreements about the relevant moral principles. Instead of clarifying whether we’re concerned with well-being, autonomy, rights, or some other deontological constraint, they blur these different concerns into the emotional appeal. For careful philosophical analysis, this is a dead end. We should be wary of any fast rhetorical flourish that preempts the hard work of examining premises, weighing evidence, and addressing arguments and counterarguments.

Another example of a thought-stopping slogan that I heard while attending a protest was “From the river to the sea” which has become a rallying cry in some pro-Palestinian activism. Perhaps I should simply take the slogan to express a vision of freedom and justice for Palestinians. However, it also carries connotations of eliminating the state of Israel altogether, a worrying implication that is often left unexamined and just shouted out loud during these protests. In general, slogans often take a maximalist position that is hard to square with compromise, tradeoffs, or moral considerations that pull in opposite directions and that we have to weigh up.

Some others:

“Defund the police.”

“We should aim for degrowth.”

“Eat the rich.”

Why they feel appealing: Motivates people because it promotes radical and fast change, and the change is supposedly material, in terms of shifting money and resources away from some institution (such as the police, or a particular part of the economy) and towards another.

The problem: They have completely elastic meanings. When people are forced to pin down their concrete or exact policy proposal, it can range from small budget trimming to the abolition of an entire system. Some people do want to defund the police, some others just want to reduce police corruption. Some people do want degrowth, some others are just a bit concerned about the environment and want green growth. Some people want to eat th-… well, kill the rich, some others just want them paying more taxes. No two people seem to have the same interpretation of what the slogan would entail. This vagueness prevents people from ever refuting the idea, playing an endless game of ideological whack-a-mole, which makes the meme stick around.

Why These Devices Persuade.

Three reasons why I think using metaphor, analogy, fiction and slogans are so convincing:

Cognitive ease / Laziness. One vivid similarity offers an easily usable mental shortcut and removes the ambiguity, while evaluating the argumentative dissimilarities is more cognitively costly.

Moral emotions such as anger, disgust, pride, and nostalgia give a false sense of clarity, and motivate to action.

Displaying coalitional signalling. Endorsing a slogan or particular metaphor broadcasts group membership, and accuracy is secondary. Further, the repetition in TV and social media feeds can make the metaphor feel real and factual.

Takeaways for rigorous argumentation.

Metaphors and slogans are not forbidden, but should be mostly seen as placeholders for an argument you owe the audience. Before leaning too much on one, perhaps:

Evaluate (and perhaps list out) the different dimensions of similarity and difference.

Try to show that the similarities are decision-relevant, not superficial or cosmetic.

Stress-test the policy conclusion under the most important disanalogies. Try to see them from the point of view of someone who disagrees that the analogy applies.

If an analogy survives that gauntlet, keep it, and maybe you can find the common principle they share, and then make the underlying model explicit so others can check your work. At that point, you can even throw away the analogy, and just use it for newcomers or laypeople to get a good, quick grasp on the topic.

Recommended readings.

Refusing to Quantify is Refusing to Think (About Tradeoffs), by Richard Chappell.

Analytic vs Conventional Bioethics - Richard Chappell on, roughly, how bioethicists use slogans instead of arguments, which I believe can cause actual harm.

The Memefication of Thought - Bentham's Bulldog about the problem of using memes instead of thinking argumentatively.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By - Classic work on the pervasiveness of metaphor in our conceptual systems.

Haidt, J. The Righteous Mind (2012) and The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail - Develops Haidt’s Moral Foundation Theory and phenomenon of moral dumbfounding, where people appeal to emotions such as disgust yet can’t explain why such a moral action is wrong.

Greene, J. Moral Tribes (2013) and The Secret Joke of Kant’s Soul (2007) - Argues that many deontological intuitions are emotional reactions to contact and bodily harm, and thus unreliable.

You are right that those closest to EA and Rationalism would like this post. While thatis my own case, I'll take the opportunity to nitpick the overall theme. In a way, it feels (pardon the simile/metaphor) like a replay of a perennial theme since, at least, the Greeks, i.e., the tension between philosophy and rhetoric, Socrates-Plato and the sophists, epistemology and truth-seeking versus politics and persuasion and power seeking, Analytical versus Continental philosophy. There is, in fact, a trade-off at play here between being really truthful and precise and between being persuasive and seductive. Everything you say is true, but it is also true that those who haven't been trained and-or aren't amenable to pure, rational, logical argumentation (likely the vast majority of people) will mostly be impervious to what you say. And I also feel this is a particular Achilles Heel of Rats and EAs, who on average aren't very good at social skills and the arts of politics and persuasion to begin with.